Happy Monday Uplifting Family,

I've loved the comments coming back from last week's excerpt from Chapter 2! So many of you are passionate about your current team. You appreciated the recognition that the quality of experiences we design externally is a reflection of the culture of empathy and excellence we foster internally. So as a gift to you and your team, here is a manifest mad-lib banner I created to help your team crystallize your purpose. If you want to get a physical version, then head over to the Swag area of the site :).

This week I'm sharing an excerpt from Chapter 3, which is all about the values of the people you serve through design!

Happy reading,

// dan

Dan Makoski // Chief Design Advisor

Uplifting.Design

Chapter 3 - Them

In the last two chapters we explored personal and team values. As important as those are, we’re now getting to the truly special ingredient: the values of the people you are designing for. This is who I am referring to by the title of this chapter: “Them”. After all, great design is about thoughtfully improving lives. I conveniently titled this chapter because it fits the other two chapters of “You” and “Us”, and also because an unhealthy “us and them” tension exists in most businesses.

Think about how businesses describe the people they serve. They use terms like “consumer”, “target”, “customer”, “segment” or “user”. People are so much richer than those definitions. They have lives, hopes, fears, goals and relationships. Yale design professor Edward Tufte notes that there are only two industries that describe their customers as “users”: drugs and computers. Describing the people we serve in functional or commercial ways relegates them to a unit of economic or product transaction.

While businesses have a responsibility to generate bottom line profits ("bottom line" typically refers to the net profit or loss after all revenues and expenses have been accounted for, reflecting the overall financial performance of a company or organization), they also have responsibilities to society and the environment. Many companies have embraced this shift to what is called triple bottom line thinking, or the “three P’s”. The first and obvious P is profit, and the other two P’s are people and planet. The rapid emergence of Chief Diversity Officers and Chief Sustainability Officers are a testament to this shift.

I hope the shift continues to the point where we describe people in richer ways and “consumer” will seem like an outdated label of the past. In the entire world of healthcare, we call people “patients”. This is a word that describes someone in a poor state of health, and the dictionary definitions include words like sufferer, invalid, sick, ill, etc. There is no word in the English language that describes a human being’s potential to get, live and feel better. It would be like a sports coach not having the word athlete in their vocabulary, only being able to describe their players as “injured”. So our design team invented a word. We started calling people “wellbeings”.

These words are meaningless, or even incorrect, from a grammatical perspective. This design critique of our business language is about a deeper reckoning with our mindset and way of thinking. Design leaders at all levels are champions for a human-centered approach, and it starts with a new way of thinking of people. A transition to this thinking would have me rename this chapter to “Us+”. The people we design for are our richest source of inspiration and innovation. As such they are really the most important members of the team, but they are often excluded from the most important parts of the design process. There may be some initial insights into people at the start of a design project from quantitative market research, and perhaps if you’re lucky even some qualitative design research to inspire brainstorming, but then people are left out of the real magic in the middle until there is something to evaluate at the end.

This is what I call the empty design research sandwich. A bit of collaboration with people at the beginning and the end, but nothing really substantial in the middle. I understand the resistance. There is a perception that design research takes too much time and is too costly. And there is a more insidious and unspoken belief that “users” don’t know what they want. The corollary to this belief is that we should trust the leaders and geniuses within the company instead. I know this belief well, as I thought I was one of those geniuses when I landed a job at the hottest design firm in the world when I was in my 20’s.

I had just started on my first project at Studio Archetype in New York City. Clement Mok started the company after leaving Apple as a Creative Director. He was one of the first design leaders to truly embrace the new technologies of the World Wide Web, multimedia programming and software as proper design spaces, as many old-school graphic designers pooh-poohed the lack of layout control and precision in these new worlds. He was profiled in a book I read while at Tufts University pursuing a degree in International Relations. The book was called “Information Architects” by Richard Saul Wurman (founder of the TED conferences), and it changed the trajectory of my career. I became fascinated with designers who were working with massive amounts of data and software design to make the complex clear, and I started to idolize the work of Studio Archetype. I sent the New York City Managing Director a hand-made sketchbook to get an interview. I showed up in the first suit of my life (and the only one dressed like that in the studio), but was clearly passionate about the company, and Donald Chesnut (now Chief Experience Officer of GM) gave me my first proper job out of university.

That first project at Studio Archetype was a massive redesign of the United Airlines website. Hundreds of thousands of pages and dozens of complex interactions. Clearly the skills of genius information architects like myself were needed! A few weeks into the project I was surprised to see that a new design researcher (whatever that was, I thought) on the project had recruited a dozen United.com travelers to come into the office and were having one-on-one creative interviews. They were giving travelers a print out of a blank browser window and asking what United.com would look like if it knew them perfectly. Travelers were a bit hesitant at first, but began filling in the paper with conversation bubbles like “Hi Yolanda, welcome back.”, sketches of upcoming trips, and links to the things they cared about most. It was messy and sometimes fantastical.

I was a bit peeved. This was the stuff I was supposed to figure out as the expert designer! I had just received my brand new business cards that said, Dan Makoski - Experience Designer, and I felt pretty darn great about them. But something unexpected happened. Over the next 9 months I was humbled by seeing the insights from that traveler research solve some of the hardest information architecture issues we faced in the redesign. At the end of the project I took that design researcher out to lunch and asked him to teach me about these superpowers he had.

John Payne then opened my eyes to the amazing world of design research, and introduced me to the work of Dr. Elizabeth (or Liz) Sanders. She was one of the first social scientists to work in a design agency (Fitch), and pioneered participatory design methods in design research. I read one of her papers where she said the following:

“There is no such thing as Experience Design.”

Dr. Liz Sanders

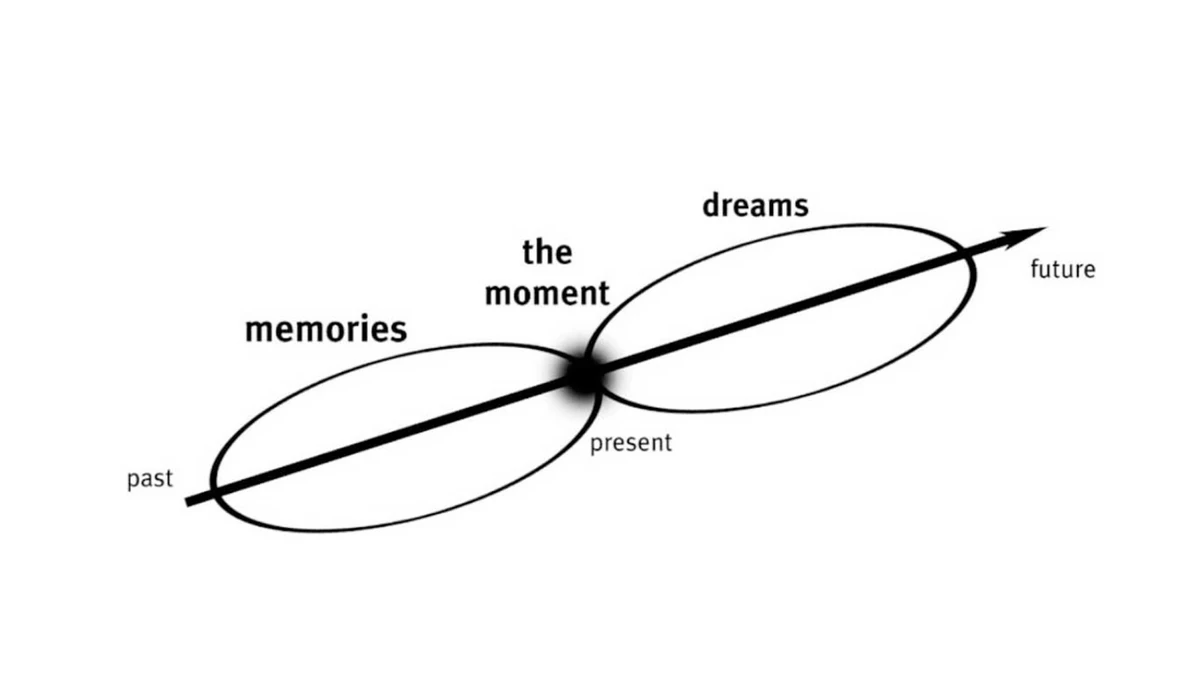

As excited as I was to explore this new world of design research, I was peeved yet again! Remember the business card I had just received? So I explored more. Liz defined an experience as a personal internal moment at the intersection of our memories of the past and our dreams of the future. Experiencing is in people. It is nuanced, and we can barely fully understand our own experiences. In this way, we cannot design an experience for someone else. It belongs to them.

Dr. Liz Sanders model of experience.

However, Liz did then go on to say that you can design for experience. That one, three-letter word completely changed my perspective on what design is all about. With this profound definition of experience, how could designers be so egotistical as to imagine that they were in control and could design the experiences of others? From that point forward, I have designed from a place of humility and awe of the experiences of the people we have the privilege to create for. I try to understand as much as I can about them. I try to always involve them in every phase of the design process, as if they are just part of the team. And above all, I ensure that their values are a core part of any team I’ve led.